✍ Sulaiman Mueez Researcher-Pakistan

The recent monsoon rains and floods in South Asian countries have again exacerbated climate insecurity in South Asia. The urban flooding, property damage, and loss of life have demonstrated the ill-equipped adaptability of these countries in the face of climate-induced problems. Despite the seriousness of climate change to human and state security, the region in general and Pakistan, India in particular, lack a comprehensive counter-framework to respond to climate disasters. The reason for this is simple: the mistrust and geopolitical tensions between Pakistan and India that influence any attempt at regional cooperation. Over the past 78 years, their shared history has been marked by persistent conflict and strategic rivalry, with only brief periods of limited cooperation. This geopolitical competition has prevented both sides from developing mutual understanding to view their security in a collective framework. Although both sides understand the risk of climate change to their collective security, no serious diplomatic attempt was made to acknowledge this fact. While the leaders of both countries preach sustainability on the global stage, they continue to treat climate cooperation as secondary to strategic rivalry at home. In COP29 in Baku last year, leaders of Pakistan and India highlighted the urgency of climate change and proposed several measures to counter the adverse effects of weather-induced disasters. However, the preposition at home for developing a regional multilateral cooperation never became the subject of discussion.

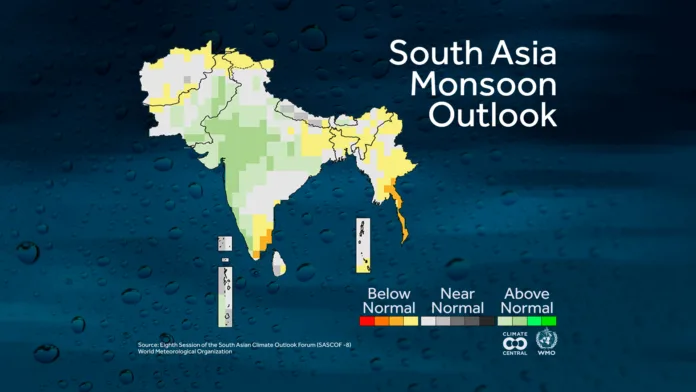

South Asia is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change. UNICEF’s Children’s Climate Risk Index report indicated that children in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan are especially vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change. Rising sea levels in the Maldives pose a threat to entire towns. The monsoon rains have swept several cities in Pakistan’s Punjab with flash floods and resulted in deaths of more than 200 people, including 104 children, since June 26. Rain continues to pour in KP and GB provinces, resulting in landslides in hilly areas. Similarly, in India, monsoon rains killed at least 30 people in northeastern states, and flash floods in Ajmer Sharif swept away vendor carts, vehicles, and people after constant rains since the start of June. On August 20, 2024, excessive rains combined with the release of water from upstream in India caused serious flooding in numerous areas of Bangladesh. On August 23, the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief reported that the floods had affected 4.5 million people. In Nepal, A mountain river flooded by monsoon rains swept away the main bridge connecting Nepal to China, leaving 20 people missing. The monsoon rain starting from May 28 has resulted in deaths of 31 people in monsoon-related incidents. Similar monsoon incidents have occurred in Sri Lanka in last year. All major South Asian countries, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, are facing severe and escalating climate threats, including glacial melt, coastal flooding, and extreme heat. Despite these common vulnerabilities, significant regional cooperation on climate security is essentially non-existent, hampered by geopolitical rivalries and mistrust.

India has been pioneering climate finance and positioning itself as a global climate leader for the developing world as India declared the US pledge of 300$ billion by 2035 insufficient for climate mitigation efforts in COP29. Despite this fervour for climate mitigation, India’s geopolitical posture with its South Asian neighbour runs counter to the spirit of regional cooperation. The militarization of Ladakh degraded the ecosystem of the Himalayas. India’s dispute with Bangladesh on the Teesla River has been a major diplomatic concern as the river flows downstream from India, and in the absence of any institutional mechanism, has only increased mistrust. Similar geopolitical issues persist with both Nepal and Pakistan, which have only undermined any prospects for regional cooperation.

After the 2022 floods that displaced millions of people, Pakistan suffered $30 billion loss and 2000 deaths from flash floods across the country. In the aftermath of the flood, Pakistan popularized climate justice to bring attention to the inequalities between the least affected developed countries and how the least emission-producing countries are the most affected by climate change. Pakistan also co-hosted the International Conference on Climate Resilient Pakistan in Geneva in 2023, to secure fund pledges for reconstruction and resilience. However, this eagerness for climate mitigation and resilience has remained absent from regional multilateral cooperation. Despite suffering from climate-induced catastrophe, Pakistan has largely avoided any engagement with India on shared ecological threats. Any hope for future developments was also derailed after recent Indian provocation and border conflict between both countries. India then unilaterally scrapped the Indus Water Treaty that had survived decades of hostility and 3 wars. Due to the persistent geopolitical rivalry between India and Pakistan, SAARC has been rendered largely ineffective, while smaller South Asian states lack the leverage to advance a collective framework for climate mitigation.

South Asia’s security dynamics have historically been shaped by global power rivalries, such as the Cold War in the 20th century, or the enduring geopolitical tensions between India and Pakistan. However, climate change is slowly influencing this factor. The predictable rain pattern and glacier melts, and freezing seasons are becoming unstable and unpredictable, and weather disasters are increasingly becoming structural. Yet, the shared recognition of climate threats is overshadowed by the region’s complex security architecture, where geopolitical rivalries dominate. In this context, climate security remains secondary, subordinated to national security priorities shaped largely by enduring regional tensions. SAARC presented a National Action Plan for climate change mitigation efforts in the 2008 summit of heads of state. That plan asserted the importance of implementing policies and developing a framework for 3 years to set an initial direction for climate cooperation. Nevertheless, that vision failed to materialize, as ongoing hostilities between India and Pakistan, coupled with the institutional stagnation of SAARC, hindered any substantial implementation. This has resulted in the region lacking a cohesive framework for climate security, despite the marked rise in both the intensity and frequency of climate-induced disasters.

The ongoing monsoon rains in Pakistan and India and resulting floods highlight the intensity of the climate-induced disasters in the region. South Asia persistently suffers from rapid urbanization, population boom, deforestation, and ecological deterioration that is further exacerbated by climate change. There is an urgent need to recognize this issue as a separate and primary threat to regional security, not just a secondary concern, which is employed as a rhetorical tool at global platforms for resource funding. South Asian countries need to revive regional climate diplomacy, depoliticize the shared resources, such as water resources and land disputes, and operationalize climate-oriented confidence-building measures. SAARC, or any alternative multilateral platform, must be revived or newly established with the urgent mandate to recognize climate change as a core component of South Asia’s shared security, requiring states to set aside narrow self-interest in favor of collective resilience. Otherwise, climate security will continue to suffer unless climate change is recognized as a regional strategic concern, rather than merely a subject for diplomatic discourse.